Lawrence’s Corfu memoir, Prospero’s Cell, was published in 1945, eleven years before his younger brother Gerald’s more famous memoir, My Family and Other Animals. Though Gerald’s memoir is structured around his nuclear family, and Lawrence’s does not mention his mother or siblings (except for Leslie), there are several characters and situations that appear in both books.

Lawrence’s description of Spiro Americanos, the Corfiot taxi driver who became a friend of the family, is like a deft and beautiful pencil sketch compared with Gerald’s later comic caricature:

…his Brooklyn drawl, his boasting, his coyness; he combines the air of a chief conspirator with a voice like a bass viol. His devotion to England is so flamboyant that he is known locally as Spiro Americanos. Prodigious drinker of beer, he resembles a cask with legs; coiner of oaths and roaring blasphemies, he adores little children and never rides out in his battered Dodge without two at least sitting beside him listening to his stories.

In My Family, Spiro is a primarily a comic figure, and one that is constantly in the background: he drives young Gerry about, helps Mother with the shopping, and even brings the family’s mail. He’s often cast in the role of the lovable fool, a foil. If he has a life beyond the Durrell family, we don’t know about it: Gerald does not mention Spiro’s wife or children (though he must have met them) in any of his three Corfu books.

Here’s how Gerald describes the family’s first meeting with Spiro in My Family:

…we saw an ancient Dodge parked by the kern, and behind the wheel sat a short, barrel-bodied individual, with ham-like hands and a great, leathery, scowling face surmounted by a jaunty-tilted peaked cap. He opened the car door, surged out onto the pavement, and waddled across to us.

Look at the similarities in the descriptions: like Lawrence, Gerald also immediately associates Spiro with his old Dodge car; he is a “barrel” (compared with Lawrence’s “cask”).

Later, Gerald describes Spiro as a “great brown ugly angel”, who protects the family.

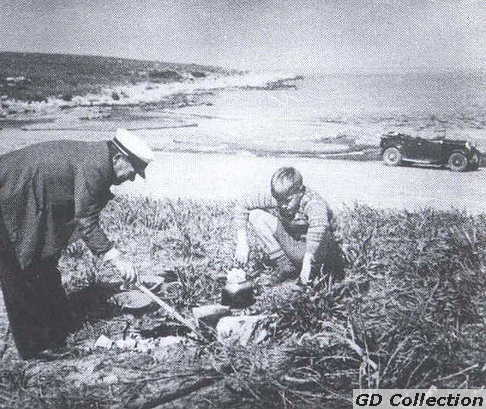

Lawrence, however, shows us a different side of Spiro, beyond his role as a character in the Durrell family saga. In Prospero’s cell, Lawrence recalls how Spiro once gathered flowers at 4 in the morning for the English wife of a seaplane pilot (one of the seaplanes Theodore so loved to watch land), near Gouvino Bay, close to the Daffodil Yellow Villa.

…it is the kind of little devotion that touches the raw heart of Spiro as he pants and grunts up the slopes of canon, his big fists full of wet flowers, and his sleepy mind thinking of the English girl who tomorrow will touch the lovely evidence of this island’s perpetual spring. Spiro is dead.

Spiro’s death “in his own vine-covered house” during the war is also recorded by Henry Miller in his Corfu travel book, The Colossus of Maroussi. Gerald never mentioned the fate of his Corfu friends, perhaps because he could not bear to.