I hope this is readable as an image – it’s a JPG of a 1982 interview with Durrell in Paris. It’s an Associated Press (AP) interview (printed in the Regina Leader-Post – but not written for them, just purchased by them from AP). Click on the image to enlarge.

Tag Archives: Henry Miller

Review: Amateurs in Eden

Finally – a chance to review (well, partially – I would like to write more later) Joanna Hodgkin’s biography of her mother, and Lawrence Durrell’s first wife, Nancy Myers.

I bought the book on Kindle, which saved me the excessive shipping costs, but as with all Kindle books loses out a bit when it comes to viewing the photographs. However, some of the photographs can be seen on Joanna’s fantastic website.

I imagine that many biographers become close to their subjects – if they did not feel an affinity with them before they began to write – but Hodgkin’s book is slightly different in that her biography of Nancy (it’s impossible to call her anything else!) is also very much a journey to understanding her mother. It is also a very touching and deeply loving tribute to a woman who, with almost “Stalinist efficiency”, as Hodgkin puts it, was almost completely airbrushed out of the Durrell family story.

Hodgkin succeeds, I think, in bringing Nancy to life as an individual, an artist, a woman and a complex, contradictory human being and not just a beautiful silent consort to a literary genius, a mysterious figure half-glimpsed through abbreviated allusions to “N”. This is not an academic biography, it’s very personal, a memoir and I do feel like I know Nancy, now!

She argues that Nancy was misunderstood, or at least misrepresented, either during her marriage to Lawrence Durrell or afterwards in memoirs.

It was particularly, Hodgkin says, during the time Nancy and Lawrence spent in Paris in the court of Henry Miller and Anais Nin that “gave rise to most of the misconceptions” about her mother.

“Several people commented on her silences and reserve,” Hodgkin writes, “and Betty Ryan, the young American artist whose flat they first stayed in, even went so far as to say she lacked ‘spark’ and kept herself aloof.”

People assumed Nancy was naturally shy and overshadowed by her vivacious, brilliant husband, Hodgkin adds, whereas the reality was “more complex” (when is it ever not?)

It was Larry, as Hodgkin calls him, who set out from the beginning to dominate the Villa Seurat – and who pushed Nancy back deliberately while fascinating his friends.

Nancy’s early years – particularly her time as a student in London before she met Durrell – are the most amusing section of the book, and show Nancy’s determination and resilience as well as her dawning realization that she is something of a beauty!

For those who read and loved Gerald Durrell’s Corfu books, then later realized ‘Brother Larry’ had a wife, the section of the book dealing with those years provide an interesting perspective – Hodgkin tries (and succeeds as far as possible) to plead her mother’s case and to give Nancy’s perspective. It’s clear that the Corfu years shaped Lawrence Durrell as a writer, and Nancy must have played an important role there.

Surprisingly, despite what Hodgkin calls Nancy’s “passion for honesty” and the fact that Gerald did not mention her at all in the book, Nancy was “charitable” to the memoir, according to Hodgkin.

Not just Nancy, but all women apart from Gerald’s sister Margo are excised from the story, Hodgkin notes.

“George Wilkinson appears as Gerry’s tutor, but there is no Pam [George’s wife]. Theodore is a childless bachelor and Larry never even has a girlfriend,” she writes.

While Gerald portrays his beloved mother as spending hours in the kitchen cooking up delicious, exotic meals for her offspring, Hodglkin tells us that Mrs. Durrell was often joined by Nancy and Pam. Perhaps the omissions are more a reflection on young Gerald’s adoration of his mother, who in his memory must have expanded to include all older women.

Interesting for me, also, that Nancy ended up in Jerusalem!

Anyway, I enjoyed Hodgkin’s writing, and would like to try one of her fiction books.

Gerald Durrell, unexpected poet

Although it is Lawrence, and not Gerald Durrell who is known for his poetry, Gerald also had a talent for verse.

On Corfu, one of his tutors, Pat Evans (a friend of Lawrence’s) taught the young Gerald literature and the boy wrote several poems that show some talent. At the tender age of eleven, Gerald wrote a poem, ‘Death’, which Lawrence included in a letter to Henry Miller:

On a mound a boy lay

While a stream went tinkling by.

Mauve irises stood round him as if to

Shield him from the eye of death

Though as an adult Gerald never wrote poetry and said that his many books were written only for money, his writing talents still shone through and one of the most beautiful pieces he wrote was perhaps a love letter to Lee McGeorge, who would become his second wife. In a 1992 interview, Gerald described in rather prosaic terms how, in 1977, he met McGeorge, then a PhD student at Duke University.

I’d been married before and was on the point of getting divorced. I kept my ex-wife waiting a couple of years because I refused to be divorced on grounds of cruelty. If I’d known I was going to meet Lee I would have hurried the whole procedure through much more quickly.

I was very disappointed with my first marriage. I’m not pointing fingers at anybody. But we were married for 25 years, which is a long time.

After my wife left me, I thought: ‘Well, OK. Now let’s play the field. To hell with it. I don’t want anything more to do with women except in bed.’ I suppose it was rather an arrogant attitude to adopt. But it was the result of being hurt. But then, of course, I met this creature, and made the fatal mistake of falling in love with her.

Here’s the text of Gerald’s beautiful and moving letter – it was published in Douglas Botting‘s official biography of Durrell. It’s long, but it’s worth reading:

I have seen a thousand sunsets and sunrises, on land where it floods forest and mountains with honey coloured light, at sea where it rises and sets like a blood orange in a multicoloured nest of cloud, slipping in and out of the vast ocean. I have seen a thousand moons: harvest moons like gold coins, winter moons as white as ice chips, new moons like baby swans’ feathers.

I have seen seas as smooth as if painted, coloured like shot silk or blue as a kingfisher or transparent as glass or black and crumpled with foam, moving ponderously and murderously.

I have felt winds straight from the South Pole, bleak and wailing like a lost child; winds as tender and warm as a lover’s breath; winds that carried the astringent smell of salt and the death of seaweeds; winds that carried the moist rich smell of a forest floor, the smell of a million flowers. Fierce winds that churned and moved the sea like yeast, or winds that made the waters lap at the shore like a kitten.

I have known silence: the cold, earthy silence at the bottom of a newly dug well; the implacable stony silence of a deep cave; the hot, drugged midday silence when everything is hypnotized and stilled into silence by the eye of the sun; the silence when great music ends.

I have heard summer cicadas cry so that the sound seems stitched into your bones. I have heard tree frogs in an orchestration as complicated as Bach singing in a forest lit by a million emerald fireflies. I have heard the Keas calling over grey glaciers that groaned to themselves like old people as they inched their way to the sea. I have heard the hoarse street vendor cries of the mating Fur seals as they sang to their sleek golden wives, the crisp staccato admonishment of the Rattlesnake, the cobweb squeak of the Bat and the belling roar of the Red deer knee-deep in purple heather. I have heard Wolves baying at a winter’s moon, Red Howlers making the forest vibrate with their roaring cries. I have heard the squeak, purr and grunt of a hundred multi-coloured reef fishes.

I have seen hummingbirds flashing like opals round a tree of scarlet blooms, humming like a top. I have seen flying fish, skittering like quicksilver across the blue waves, drawing silver lines on the surface with their tails. I have seen Spoonbills flying home to roost like a scarlet banner across the sky. I have seen Whales, black as tar, cushioned on a cornflower blue sea, creating a Versailles of fountain with their breath. I have watched butterflies emerge and sit, trembling, while the sun irons their wings smooth. I have watched Tigers, like flames, mating in the long grass. I have been dive-bombed by an angry Raven, black and glossy as the Devil’s hoof. I have lain in water warm as milk, soft as silk, while around me played a host of Dolphins. I have met a thousand animals and seen a thousand wonderful things… but –

All this I did without you. This was my loss.

All this I want to do with you. This will be my gain.

All this I would gladly have forgone for the sake of one minute of your company, for your laugh, your voice, your eyes, hair, lips, body, and above all for your sweet, ever surprising mind which is an enchanting quarry in which it is my privilege to delve.

coiner of oaths and roaring blasphemies

Lawrence’s Corfu memoir, Prospero’s Cell, was published in 1945, eleven years before his younger brother Gerald’s more famous memoir, My Family and Other Animals. Though Gerald’s memoir is structured around his nuclear family, and Lawrence’s does not mention his mother or siblings (except for Leslie), there are several characters and situations that appear in both books.

Lawrence’s description of Spiro Americanos, the Corfiot taxi driver who became a friend of the family, is like a deft and beautiful pencil sketch compared with Gerald’s later comic caricature:

…his Brooklyn drawl, his boasting, his coyness; he combines the air of a chief conspirator with a voice like a bass viol. His devotion to England is so flamboyant that he is known locally as Spiro Americanos. Prodigious drinker of beer, he resembles a cask with legs; coiner of oaths and roaring blasphemies, he adores little children and never rides out in his battered Dodge without two at least sitting beside him listening to his stories.

In My Family, Spiro is a primarily a comic figure, and one that is constantly in the background: he drives young Gerry about, helps Mother with the shopping, and even brings the family’s mail. He’s often cast in the role of the lovable fool, a foil. If he has a life beyond the Durrell family, we don’t know about it: Gerald does not mention Spiro’s wife or children (though he must have met them) in any of his three Corfu books.

Here’s how Gerald describes the family’s first meeting with Spiro in My Family:

…we saw an ancient Dodge parked by the kern, and behind the wheel sat a short, barrel-bodied individual, with ham-like hands and a great, leathery, scowling face surmounted by a jaunty-tilted peaked cap. He opened the car door, surged out onto the pavement, and waddled across to us.

Look at the similarities in the descriptions: like Lawrence, Gerald also immediately associates Spiro with his old Dodge car; he is a “barrel” (compared with Lawrence’s “cask”).

Later, Gerald describes Spiro as a “great brown ugly angel”, who protects the family.

Lawrence, however, shows us a different side of Spiro, beyond his role as a character in the Durrell family saga. In Prospero’s cell, Lawrence recalls how Spiro once gathered flowers at 4 in the morning for the English wife of a seaplane pilot (one of the seaplanes Theodore so loved to watch land), near Gouvino Bay, close to the Daffodil Yellow Villa.

…it is the kind of little devotion that touches the raw heart of Spiro as he pants and grunts up the slopes of canon, his big fists full of wet flowers, and his sleepy mind thinking of the English girl who tomorrow will touch the lovely evidence of this island’s perpetual spring. Spiro is dead.

Spiro’s death “in his own vine-covered house” during the war is also recorded by Henry Miller in his Corfu travel book, The Colossus of Maroussi. Gerald never mentioned the fate of his Corfu friends, perhaps because he could not bear to.

the colossus of maroussi

The 'White House' in Kalami, now available for rent as a holiday home, and inaccurately dubbed 'the Corfu residence of Authors Gerald and Lawrence Durrell'

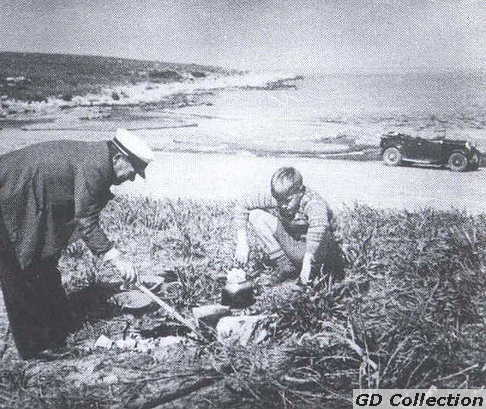

In 1939, Henry Miller visited Lawrence and Nancy Durrell in Corfu, and stayed with them in the ‘White House’ at Kalami (oddly, the house today is erroneously billed as the place where Gerald Durrell wrote My Family and Other Animals). In 1941, he published a book about his travels, The Colossus of Maroussi, in which he mentions Lawrence and Nancy frequently, offering some interesting glimpses into Nancy and Lawrence’s relationship and life on Corfu:

Durrell, and Nancy his wife, were like a couple of dolphins; they practically lived in the water.

(In Prospero’s Cell, Durrell describes Nancy as being like “an otter”, another water animal).

And later, during a trip to the Greek mainland, Miller records an exchange between the couple when their car breaks down, stranding them:

“Why don’t you try to do something?’ said Nancy. Durrell was saying, as he usually did when Nancy proffered her advice, ‘Why don’t you shut up?”

Miller also remarks on some of the Durrell family‘s friends familiar to readers of Gerald’s autobiographies – notably Spiro Amerikanos (Miller mentions Spiro’s son, Lillis – Gerald does not mention Spiro’s family at all) and Theodore Stephanides, both of whom seem to have made quite an impression on Miller.

Here Miller quotes from a letter Lillis wrote about the dying Spiro:

There was one other person whose presence I missed and that was Spiro of Corfu. I didn’t realize it then, but Spiro was getting ready to die. Only the other day I received a letter from his son telling me that Spiro’s last words were: “New York! New York! I want to find Henry Miller’s house!”. Here is how Lillis, his son, put it in his letter: “My poor father died with your name in his mouth which closed forever. The last day he lost his logic and pronounced a lot of words in English…He died as poor as he always was. He did not realize his dream to be rich.’

At the time of Miller’s wartime visit to Corfu, the rest of the Durrell family had already left the island – apart from Margaret Durrell, Lawrence’s younger sister, who had made up her mind to “sit out” the war with her Greek friends. When Lawrence and Nancy left for Athens, Miller stayed alone on Corfu and Margaret was charged with looking after him. She recalls (in an interview with Sue and Ian MacNiven recorded in Lawrence Durrell and the Greek World edited by Anna Lillios):

Henry was up in the north with Lawrence, and Henry stayed on after Lawrence went to Athens, and Lawrence asked me to look after him and he said ‘Don’t let anybody swindle him,’ which I thought was a typical Lawrence remark at that point.

Durrell and Miller, many years after Miller’s visit to Corfu.

Related articles

- Whatever happened to Nancy? (whitemetropolis.wordpress.com)